Many people visiting a Coptic Orthodox Church or one of Her sister churches witness certain practices and customs that seem alien to someone coming from a non-Orthodox or even a non-Christian background. These practices and customs include, but are not limited to, clergy wearing black, believers wearing crosses around their necks, kissing the hands of bishop and priests, and more. To help clarify questions about these practices, we have prepared the following pages as a brief introduction to some of the common customs in Orthodoxy among the faithful.

An Ancient Christian Church. It is one of the most ancient Churches in the world, having been founded by Saint Mark the Apostle, the writer of the second gospel, in the first Century. The word ‘Coptic’ comes from the ancient Egyptian word ‘hekaptah’ meaning ‘Egypt’, and thus ‘Coptic’ merely means ‘Egyptian.’ As a conservative Church, the Coptic Church has carefully preserved the Orthodox Christian Faith in its earliest and purest form, handing it down from generation to generation, unaltered and true to the Apostolic doctrines and patterns of worship.

Trinitarian. She believes in the Holy Trinity: Father, Son and Holy Spirit (being one God); and that our Lord, God and Savior Jesus Christ, the true Son of God, became incarnate, was born of the Virgin Saint Mary, died for us on the Cross that He may grant us Salvation, rose on the third day that He may grant us everlasting life with Him, and ascended to heaven after forty days, sending the Holy Spirit to His disciples as He promised them, on the day of Pentecost.

Apostolic. She was founded by Saint Mark the Apostle and Evangelist who preached to the Egyptians around 60-70 A.D.

Scriptural (Biblical). Her main point of reference is the Holy Scripture, as depicted in literal translations such as King James (KJV), New King James (NJKV), and the Revised Standard Version (RSV). Although the Coptic Orthodox Church accepts any New Testament translation that is faithful to the Greek Textus Receptus translation, She prefers only the Septuagint (LXX) translation of the Old Testament and not the Masoretic text found in most Bibles today.

Traditional. One of the pillars of her faith is the teachings of the early Church Fathers as well as the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed as a statement of Her Faith.

Sacramental. She has seven primary Mysteries: Baptism, Chrismation, Confession, the Eucharist (Communion), Marriage, Priesthood, and the Anointing of the Sick.

Conservative. She does not change basic matters of Faith, Dogma or Tradition to suit current trends (this does not mean however that matters such as language and day-to day practices are not changed to suit conditions of ministry and the needs of the congregation). Holding on to such matters of Faith and practice has not been an easy task, as the Coptic Church has always lived persecution of one form or another since its establishment in the first century.

St. Mark, The Founder

The Copts are proud of the apostolicity of their Church, whose founder is St. Mark, one of the seventy Apostles (Mk 10:10Open in Logos Bible Software (if available)), and one of the four Evangelists. He is regarded by the Coptic hierarchy as the first of their unbroken 117 patriarchs, and also the first of a stream of Egyptian martyrs. This apostolicity was not only furnished on grounds of its foundation but rather by the persistence of the Church in observing the same faith received by the Apostle and his successors, the Holy Fathers.

St. Mark’s Bibliography

St. Mark was an African native of Jewish parents who belonged to the Levites’ tribe. His family lived in Cyrenaica until they were attacked by some barbarians, and lost their property. Consequently, they moved to Jerusalem with their child John Mark (Acts 12:12Open in Logos Bible Software (if available), 25Open in Logos Bible Software (if available); 15:37Open in Logos Bible Software (if available)). Apparently, he was given a good education and became conversant in both Greek and Latin in addition to Hebrew. His family was highly religious and in close relationship with the Lord Jesus Christ. His cousin was St. Barnabas and his father’s cousin was St. Peter. His mother, Mary, played an important part in the early days of the Church in Jerusalem. Her upper room became the first Christian church in the world where the Lord Jesus Christ Himself instituted the Holy Eucharist (Mk 14:12-26Open in Logos Bible Software (if available)). Also, this is the same place where the Lord appeared to the disciples after His resurrection and His Holy Spirit came upon them.

Young Mark was always associated with the Lord, who choose him as one of the seventy. He is mentioned in the Holy Scriptures in a number of events related with the Lord. For example, he was present at the wedding of Cana of Galilee, and was the man who had been carrying the jar when the two disciples went to prepare a place for the celebration of the Passover (Mk 14:13-14Open in Logos Bible Software (if available); Lk 22:11Open in Logos Bible Software (if available)).

The voice of the lion is the symbol of St. Mark for two reasons:

1. He begins his Holy Gospel by describing John the Baptist as a lion roaring in the desert (Mk 1:3Open in Logos Bible Software (if available)).

2. His famous story with lion, as related to us by Severus Ebn-El-Mokafa:

Once a lion and lioness appeared to John Mark and his father Arostalis while they were traveling in Jordan. The father was very scared and begged his son to escape, while he awaited his fate. John Mark assured his father that Jesus Christ would save them and began to pray. The two beasts fell dead and as a result of this miracle, the father believed in Christ.

Preaching with the Apostles

At first, St. Mark accompanied St. Peter on his missionary journeys inside Jerusalem and Judea. Then he accompanied St. Paul and St. Barnabas on their first missionary journey to Antioch, Cyprus and Asia Minor, but for some reason or another he left them and returned home (Acts 13:13Open in Logos Bible Software (if available)). On their second trip, St. Paul refused to take him along because he left them on the previous mission; for this reason St. Barnabas was separated from St. Paul and went to Cyprus with his cousin St. Mark (Acts 15:36-41Open in Logos Bible Software (if available)). There, he departed in the Lord and St. Mark buried him. Afterwards, St. Paul needed St. Mark with him and they both preached in Colosse (Col 4:10Open in Logos Bible Software (if available)), Rome (Phil 24; 2 Tim 4:11Open in Logos Bible Software (if available)) and perhaps in Venice.

In Africa

Coptic Cathedral of St. Mark in Alexandria, EgyptSt. Mark’s real labor lays in Africa. He left Rome to Pentapolis, where he was born. After planting the seeds of faith and performing many miracles he traveled to Egypt, through the Oasis, the desert of Libya, Upper Egypt and then entered Alexandria from its eastern gate in 61 A.D.

On his arrival, the strap of his sandal was loose. He went to a cobbler to mend it. When the cobbler – Anianos – took an awl to work on it, he accidentally pierced his hand and cried aloud “O One God”. At this utterance, St. Mark rejoiced and after miraculously healing the man’s wound, took courage and began to preach to the hungry ears of his convert. The spark was ignited and Anianos took the Apostle home with him. He and his family were baptized, and many others followed.

The spread of Christianity must have been quite remarkable because pagans were furious and ought St. Mark everywhere. Smelling the danger, the Apostle ordained a bishop (Anianos), three priests and seven deacons to look after the congregation if anything befell him. He left Alexandria to Berce, then to Rome, where he met St. Peter and St. Paul and remained there until their martyrdom in 64 A.D.

Upon returning to Alexandria in 65 AD, St. Mark found his people firm in faith and thus decided to visit Pentapolis. There, he spent two years preaching and performing miracles, ordaining bishops and priests, and winning more converts.

Finally he returned to Alexandria and was overjoyed to find that Christians had multiplied so much that they were able to build a considerable church in the suburban district of Baucalis.

His Martyrdom

In the year 68 AD, Easter fell on the same day as the Serapis feast. The furious heathen mob had gathered in the Serapis temple at Alexandria and then descended on the Christians who were celebrating the Glorous Resurrection at Baucalis. St. Mark was seized, dragged with a rope through the main streets of the city. Crowds were shouting “The ox must be led to Baucalis,” a precipitous place full of rock where they fed the oxen that were used in the sacrifice to idols. At nightfall the saint was thrown into prison, where he was cheered by the vision of an angel, strengthening him saying, “Now your hour has come O Mark, the good minister, to receive your recompense. Be encouraged, for your name has been written in the book of life.” When the angel disappeared, St. Mark thanked God for sending His angel to him. Suddenly, the Savior Himself appeared and said to him, “Peace be to you Mark, my disciple and evangelist!” St. Mark started to shout, “O My Lord Jesus” but the vision disappeared.

On the following morning probably during the triumphal procession of Serapis he was again dragged around the city till death. His bloody flesh was torn, and it was their intention to cremate his remains, but the wind blew and the rain fell in torrents and the populaces disperse. Christians stole his body and secretly buried him in a grave that they had engraved on a rock under the altar of the church.

His Apostolic Acts

St. Mark was a broad-minded Apostle. His ministry was quite productive and covered large field of activities. These include:

• Preaching in Egypt, Pentapolis, Judea, Asia Minor, and Italy during which time he ordained bishops, priests, and deacons.

• Establishing the “School of Alexandria” which defended Christianity against philosophical school of Alexandria and conceived a large number of great Fathers.

• Writing the Divine Liturgy of the Holy Eucharist which was modified later by St. Cyril to the Divine Liturgy known today as the Divine Liturgy of St. Cyril.

The Term “Copt” – The term “Copt” and “Egyptian” have the same meaning as derived from the Greek word aigyptos. With the suppression of the prefix, the suffix of the word, the stem “gypt” has become part of the words for “Egypt” and for “Copt” in all the modern languages of Latin origin. The Coptic Church then is simply the Egyptian Church.

The Coptic Language – It is the last shape of the language of the ancient Egyptians. The earlier shapes represented in the Hieroglyphic and Hieratic and Demotic alphabet became inaccessible to the growing needs of daily life. After the spread of Christianity, Egyptian scholars trans-literated Egyptian texts into the Greek alphabet, and adopted the last seven additional letters of the Coptic alphabet from their own Demotic.

The Founders of the Church – The Copts pride themselves on the apostolicity of their national church, whose founder was none other than St. Mark, one of the four Evangelists and the writer of the oldest canonical Gospel. John Mark is regarded by the Coptic hierarchy as the first in their unbroken chain of 117 popes. He is also the first of a stream of Egyptian saints and glorious martyrs.

Church of Martyrs – After the martyrdom of St. Mark, the Coptic Church faced severe persecutions. The seventh persecution inflamed by emperor Diocletian; his reign (284-305) is considered by the Copts as the age of persecution. Under Maximin Daia (305-313), his successor in the East, the massacre continued for eight years of systematic killing. This could account for tremendous number of martyrs. So profound was the impression of the persecution of Diocletian on Coptic life and thought that the Copts decided to adopt for church use a calendar of the martyrs, the “Anno Martyri”. The first year of that calendar was 284 A.D., the year of the disastrous accession of Diocletian.

Catechetical School of Alexandria – The school of Alexandria was undoubtedly the earliest important institution of theological learning in Christian antiquity. It was a college in which many other disciplines were studied from the humanities, science and mathematics; but its main discipline was religion. According to Eusebius, its founder was St. Mark who appointed Lustus as its dean, (later on, Lustus became the sixth patriarch). Most of the eminent leaders of Alexandria like Clement, Origen, Dionysius, Athanasius, Didymus the Blind and Cyril, were known to have been connected with it, either as teachers or students.

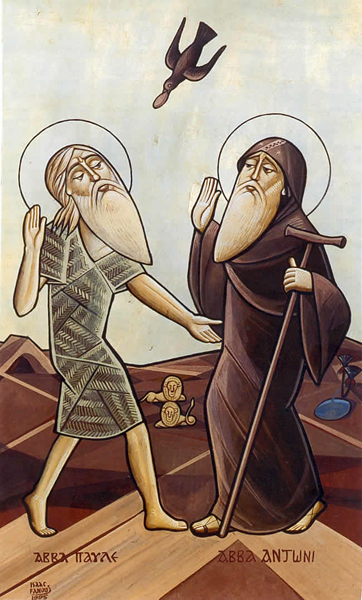

The Church of Monasticism – The Christian Church heavily indebted for the creation of monasticism which started in Egypt. Although St. Paul the Theban (died 340) is considered the first hermit, the origins of monasticism are ascribed to St. Anthony (251356) whose fame was spread by his famous biography written by St. Athanasius. The Fathers of the Church from numerous parts of the world came to Egypt for training in the way of monasticism. Monasticism has survived in Egypt and has given the Coptic Church an unbroken line of 117 Popes beginning with St. Mark. Although most of the monasteries have disappeared under the Arab persecution there is a revival in the surviving ones.

Adapted from “The Servants’ Manual” by Joseph Ibrahim

The term “Coptic” is derived from the Greek “Aigyptos” meaning “Egyptian”. When the Arabs arrived in Egypt in the seventh century, they called the Egyptians “qibt”. Thus the Arabic word “qibt” came to mean both “Egyptians” and “Christians”.

The term “Orthodoxy” here refers to the preservation of the “Original Faith” by the Copts who, throughout the ages, defended the Old Creed against the numerous attacks aimed at it.

The Coptic Orthodox Church believes that the Holy Trinity: God The Father, God The Son, and God The Holy Spirit, are equal to each other in one unity; and that the Lord Jesus Christ is the only Savior of the world. Less changes have taken place in the Coptic Church than in any other church whether in the ritual or doctrine aspects and that the succession of the Coptic Patriarchs, Bishops, priests and Deacons has been continuous.

“Blessed is Egypt my people” (Isa 19:25 )

)

God’s promise to His people is always fulfilled; He foretold that He would ride on a light and upon a swift cloud and come to Egypt (Isa 19:1 ); and in that day there will be an altar to the Lord in the midst of the land of Egypt, and a pillar to the Lord at its border (Isa 19:19

); and in that day there will be an altar to the Lord in the midst of the land of Egypt, and a pillar to the Lord at its border (Isa 19:19 ). This promise was fulfilled by the flight of the Holy Family from the face of the tyrant Herod to find refuge among the Gentiles. Thus our Lord Jesus Christ came during His childhood to Egypt to lay by Himself the foundation stone of His Church in Egypt which has become one of the four primary “Sees” in the world, among the churches of Jerusalem, Antioch and Rome, and joined later by the “See” of Constantinople.

). This promise was fulfilled by the flight of the Holy Family from the face of the tyrant Herod to find refuge among the Gentiles. Thus our Lord Jesus Christ came during His childhood to Egypt to lay by Himself the foundation stone of His Church in Egypt which has become one of the four primary “Sees” in the world, among the churches of Jerusalem, Antioch and Rome, and joined later by the “See” of Constantinople.

The star of the Egyptian Church shone through the School of Alexandria which taught Christendom the allegoric and spiritual methods in interpreting the Holy Scripture and was the leader in defending the Orthodox faith on an ecumenical level.

The Christian monastic movement in all its forms started in Egypt, attracting the heart of the Church towards the desert, to practice the angelic inner life. This happened at the time when the doors of the royal court had been opened to the clergy, and this consequently endangered the church, as the quiet and spiritual church work was mixed with the temporal authority and politics of the royal court.

The Egyptian Church carried our Lord Jesus Christ’s cross throughout generations, bearing sufferings even from the side of Christians themselves. She continued to offer a countless number of martyrs and confessors throughout ages. Sometimes the people of towns were martyred and many struggled to win the crowns of martyrdom happily and with a heart full of joy.

Our Church is ancient and new at the same time: ancient in being apostolic, founded by St. Mark the Evangelist and traditional in holding fast to the original apostolic faith without deviation. She is also new through her Living Messiah who never becomes old and through the Spirit of God who renews her youth (Ps. 103:5 ).

).

The Coptic Church is rich with her evangelistic and ascetic life, her genuine patriotic inheritance, her heavenly worship, her spiritual rituals, her effective and living hymns, her beautiful icons, etc. She attracts the heart towards heaven without ignoring actual daily life. We can say that she is an apostolic, contemporary church that carries life and thought to the contemporary man without deviation. One finds in her life, sweetness and power of Spirit, with appreciation to and sanctification of arts, literature and human culture.

The Church is well known for her numerous saints: ascetics, clergymen and laymen. She offered many saints throughout ages and is still offering the same today. For she believes that practicing the sanctified life and communion with God, the Holy One, is prior to satisfying minds with solid mental studies.

At the present time there are three Liturgies used in the Coptic Orthodox Church:

The Liturgy according to St Basil, bishop of Caesarea The Liturgy according to St Gregory of Nazianzus, bishop of Constantinople The Liturgy according to St Cyril I, the 24th Patriarch of the Coptic Orthodox Church The Liturgy according to St. Basil is the one used most of the year; St. Gregory’s Liturgy is used during the feasts and on certain occasions; only parts of St. Cyril’s Liturgy are used nowadays.

The Liturgy was composed by the Apostles as taught to them by Jesus Christ, who after His resurrection appeared to them: “to whom He also presented Himself alive after His suffering by many infallible proofs, being seen by them during forty days and speaking of the things pertaining to the kingdom of God.” [Acts 1:3Open in Logos Bible Software (if available)]

It is worth noting here that the Liturgy was first used (orally) in Alexandria by St. Mark and that it was recorded in writing by St. Cyril I, the 24th Patriarch of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Egypt. This is the Liturgy known as St. Cyril’s Liturgy and from which the other two liturgies — referred to above — are derived.

St. Mark, as we know, was one of the seventy disciples of Jesus Christ. Also, he accompanied St. Peter and St. Paul and shared the Apostolic work with them. St. Mark came to Egypt around the year 40 A.D. and established the Coptic church in Alexandria and used the above-mentioned Liturgy there. This Liturgy is one of the oldest liturgies known to the Christian world. Versions of St. Mark’s Liturgy exist in Ge’ez, the ancient language of Ethiopia, which ceased to be a living language in the 14th century A.D., but has been retained as the official and liturgical language of the Coptic Church of Ethiopia.

The sections and divisions of the three liturgies follow the same order and subject matter as taught to us by the Lord Jesus Christ: “And as they were eating, Jesus took bread, blessed it and broke it, and gave it to the disciples and said, ‘Take, eat; this is My body.’ Then He took the cup, and gave thanks, and gave it to them, saying, ‘Drink from it, all of you. For this is My blood of the new covenant, which is shed for many for the remission of sins.’” [Matthew 26:26-28Open in Logos Bible Software (if available)] This sacrament has also been mentioned by St. Paul: “For I received from the Lord that which I also delivered to you: that the Lord Jesus on the same night in which He was betrayed took bread; and when He had given thanks, He broke it and said, ‘Take, eat; this is My body which is broken for you; do this in remembrance of Me.’ In the same manner He also took the cup after supper, saying, ‘This cup is the new covenant in My blood. This do, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of Me.’ For as often as you eat this bread and drink this cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death till He comes.” [Corinthians-1 11:23-26]

The Coptic Liturgy has the following main sections, which are also characteristics of almost every Liturgy all over the Christian world:

Prayer of Thanksgiving Prayer of Consecration Prayer of Fraction Prayer of Communion The Liturgy of St. Basil the Great, Bishop of Caesarea

As we mentioned before, the Liturgy of St. Basil is the one most commonly used in the Coptic Orthodox Church. It is also widely used in the other Orthodox Churches around the world. The Basilian Liturgy was established at the end of the 4th century, and drew heavily on the Liturgy of St. Mark the Evangelist. The Basilian Liturgy is addressed to God the Father, as is St. Mark’s Liturgy (better known as St. Cyril’s Liturgy), whereas the Liturgy of St. Gregory is addressed to the Son. Vespers and Matins prayers always preceede the service of the Basilian Liturgy (the same is done with Gregory’s Liturgy or Cyril’s Liturgy).

We have to assume that the present Basilian Liturgy is somewhat different from the original one, in that certain sections (e.g. Intercessions) must have been added to it. The Basilian Liturgy, as prayed in the Coptic Orthodox Church, includes the following as its main subsections (within the 4 sections mentioned above):

Offertory: Offering of the bread (Lamb) The Circuit The Prayer of Thanksgiving Absolution The Intercessions: St. Mary, the Archangels, the Apostles, St. Mark, St. Menas, St. George, Saint of the day, the Pope and bishops. Readings: 3 Passages from Pauline Epistles, Catholic Epistles, and Acts Synexarium: The Saints of the day The Trisagion The Holy Gospel with an introductory prayer and Psalm reading. Supplications for the Church, the fathers, the congregations, the president, government, and offcials. The creed (Nicene creed of St. Athanasius, the 20th Coptic Pope) The Prayer of reconciliation Holy, Holy, Holy Crossing the offerings Prayer of the Holy Spirit invocation and outpouring. Supplications for the Church unity and peace, the fathers, the priests, the Place, the (Nile) water (or the vegetation or the Crops), and the offerings. Memory of the congregation of Saints Introduction to the sharing of the Holy Communion The fraction of the bread The profession and declaration of Orthodox faith The Holy Communion Psalm 150 and appropriate hymns (concurrently with the offering of the Holy Communion). Benediction The Eulogia The sermon (usually offered by the presiding priest) is given (if at all) right after the reading of the Gospel or at the end of the service. The Sermon, which is not an integral part of the Liturgy, offers explanations and contemplations on the Gospel.

Moses’ Law arranged seven major feasts (lev. 23), which had their rites and sanctity, as a living part of the common worship. These feasts are: the Sabbath or Saturday of every week, the first day of every month, the Seventh Year, the Year of Jubilee, the Passover (Pasch), the feast of the weeks (Pentecost), the feast of Tabernacles (feast of Harvest). After the Babylonian exile two feasts were added, i.e., the feast of Purim and the feast of Dedication. The aim of these feasts was to revive the spirit of joy and gladness in the believers’ lives and to consecrate certain days for the common worship in a holy convocation (assembly) (Exod 12:16Open in Logos Bible Software (if available); Lev. 23Open in Logos Bible Software (if available)); and to remember God’s promises and actions with His people to renew the covenant with Him on both common and personal levels. The feasts were a way leading to enjoy Christ, the continuous “Feast” and the Source of eternal joy.

When the Word of God was incarnate and became man, He submitted to the Law and attended and celebrated the feasts. However, He diverted the attention from the symbol to reality, and from the outward appearances to the inner depths (John 2, 5, 6, 7, 12); to grant the joy of the feast through practicing the secret communion with God and receiving His redeeming deeds.

Almost all the days are feasts to the Coptic Church. Although she is known for bearing the cross, she is eager to have her children live, in the midst of sufferings in spiritual gladness. She is capable, by the Lord’s help, to raise them above tribulations. In other words, the Coptic Church is continuously suffering and joyful at the same time, her feasts are uninterrupted, and her hymns with a variety of melodies are unceasing.

A Church of Joy

One of the main characteristics of the Coptic Church is “joy,” even in her ascetic life. St. John Cassian described the Egyptian monks who spread from Alexandria to the southern borders of Thabied (Aswan) saying that the voice of praise came out perpetually from the monasteries and caves, as if the whole land of Egypt became a delightful paradise. He called the Egyptian monks heavenly terrestrials or terrestrial angles.

St. Jerome informs us about an abbot called Apollo who was always smiling. He attracted many to the ascetic life as a source of inward joy and heartfelt satisfaction in our Lord Jesus. He often used to say: “Why do we struggle with an unpleasant face?! Aren’t we the heirs of the eternal life?! Leave the unpleasant and the grieved faces to pagans, and weeping to the evil-doers. But it befits the righteous and the saints to be joyful and pleasant since they enjoy the spiritual gifts.”

This attitude is reflected upon church worship, her arts and all her aspects of life, so that it seems that the church life is a continuous unceasing feast. Pope Athanasius the Apostolic tells us in a paschal letter that “Christ” is our feast. Although there are perpetual feasts the believer discovers that his feast is in his innermost, i.e., in the dwelling of Christ the life-giving Lord in him.

The church relates and joins the feasts to the ascetic life. The believers practice fasting, sometimes for almost two months (Great Lent) in preparation for the feast, in order to realize that their joy is based on their communion with God and not on the matter of eating, drinking and new clothes.

The Coptic feasts have deep and sweet hymns, and splendid rites that inflame the spirit. Their aim is to offer the living heavenly and evangelic thought and to expose the Holy Trinity and Their redeeming work in the life of the church, in a way that is simple enough to be experienced by children, and: deep enough to quench the thirst of theologians.

The Seven Major Feasts of the Lord in the Coptic Orthodox Church

The Annunciation (Baramhat 29, c. April 7): In it we recall the fulfillment of the Old Testament prophecies, and the attainment which the men of God had longed for across the ages, namely the coming of the Word of God incarnated in the Virgin’s womb (Matt. 13:17Open in Logos Bible Software (if available)). The Nativity of Christ (Christmas) on Kayhk 29, c. January 7: It is preceded by a fast of 43 days. Its aim is to confirm the divine love, when God sent His Only – begotten Son incarnate. Thus, He restored to humanity her honor, and sanctified our daily life, offering His life as a Sacrifice on our behalf. The Epiphany or the Baptism of Christ on Tobah 11, c. January 19: It is connected with Christmas and the circumcision feasts. For on Christmas, the Word of God took what is ours (our humanity) and in the “circumcision” He subjected Himself to the Law as He became one of us, but in the Epiphany He offered us what is His own. By His incarnation He became a true man while He still being the Only-begotten Son of God, and by baptism we became children of God in Him while we are human being In this feast, the liturgy of blessing the water is conducted, and the priest blesses the people by the water on their foreheads and hands to commemorate baptism. Palm Sunday: It is the Sunday which precedes Easter. It has its characteristic joyful hymns (the Shannon – Hosanna (Matt. 21:9Open in Logos Bible Software (if available)), and its delightful rite. The church commemorates the entrance of our Lord Jesus into our inward Jerusalem to establish His Kingdom in us and gather all in Him. Therefore a delighful is procession or the redeemed believers, starts -God’s plan for Christ’s self-oblation. The procession moves towards the nave of the church were it stands before the icons of St. Mary, the Archangels, St. John the Baptist, the Apostles, the marthe ascetics etc… and before the church doors and the baptismal basin, praising God who embraces all together in His Son Jesus Christ. The procession ends by re-entering the sanctuary, for the of God of the Old and New testaments meet with the heavenly in heaven (sanctuary) forever. The end of the liturgy of Eucharist, a general funeral service is held over water, which is sprinkled on behalf of anyone who may die during the Holy week, since the regular funeral prayers are not conducted during this week. By this rite, the church stresses on her pre-occupation with the passion and crucifixion of Christ only. She itrates on the marvelous events of this unique week with its glorious readings and rites which concern our salvation. Easter (The Christian Pasch or Passover): It is preceded by Great Lent (55 days) and is considered by the Coptic Church as the Feast.” Its delight continues for fifty days until the Pentecost. Easter is also essentially celebrated on every Sunday by participating A sacrament of the Eucharist. For the church wishes that all believers may enjoy the new risen life in Jesus Christ (Rom. 6:4Open in Logos Bible Software (if available)). Ascension: It is celebrated on the fortieth day after Easter Is on a Thursday. In this feast we recall Him who raises and lifts us up to sit with Him in heaven (Eph. 2:6Open in Logos Bible Software (if available)). Pentecost: It represents the birthday of the Christian Church. Only-begotten Son paid the price for her salvation, He ascended heaven to prepare a place for her. He sent His Holy Spirit in her, offering her existence, guidance, sanctification and adornment as the Heavenly Bride. In this feast, the church chants hymns, being joyful with the resurrection of Christ, His ascension and the dwelling of His Holy Spirit in her, thus she connects the three feasts in one whole unity. On this day, the church conducts three sets of prayers, called “Kneeling,” during which incense and prayers are offered on behalf of the sick, the travelers, the winds, and it gives special attention to the dormant, as a sign of her enjoying the communion and unity with Christ that challenges even death. The Seven Minor Feasts of the Lord in the Coptic Orthodox Church

The Circumcision of our Lord: It is celebrated on the eighth day after Christmas (Tobah 6, c. 14 January), by which we remember that the Word of God who gave us the Law, He Himself was subjected to this Law, fulfilling it, to grant us the power to fulfill the Law in a spiritual manner. Thus we enjoy the circumcision of spirit and that of heart (Col. 2:11Open in Logos Bible Software (if available)), instead of the literal circumcision of the flesh. The Entrance of our Lord into the Temple (Amshir 8, c. February 15): We remember that the Word of God became man and does not want us to be careless about our lives, but to set our goals early since childhood. Thus we have to work and fulfill our goals regardless of people related to us, in spite of our love and obedience to them (Luke 2:24Open in Logos Bible Software (if available)). The Escape of the Holy family to Egypt (Bashans 24, c. June 1): The Coptic Church is distinguished among all nations with this unique divine work, by the coming of our Lord to Egypt among the Gentiles. The First Miracle of our Lord Jesus at Cana (Tobah 13, c. January 12): Our Lord changed the water into wine, as His first miracle, at the wedding in Cana of Galilee, confirming His eagerness for our attaining the heavenly wedding, and granting us the wine of His exceeding love. The Transfiguration of Christ (Musra 13; c. August 19): The unity of the two testaments was manifested in this feast, for Moses and Elijah assembled together with Peter, James and John. The glory of our Lord was revealed to satisfy every soul who rises up with Him to the mountain of Tabor to enjoy the brightness of His Glory. Maundy Thursday: This is the Thursday of the Holy week. In it we commemorate the establishment of the Sacrament of Eucharist by our Lord Jesus, when He offered His Body and Blood as the living and effective Sacrifice, capable of sanctifying our hearts, granting us the victorious and eternal life. This is the only day of the Holy Week in which Sacrifice of the Eucharist is offered, and the rite of washing the feet is practiced in commemoration of what Christ did for His disciples. On this day also an unusual procession takes place, starting from the south of the church nave, during which a hymn of rebuking Jude the betrayal is chanted as a warning to us not to fall like him. Thomas’s Sunday: This is the Sunday that follows Easter; In it we bless those who believe without seeing so that all might live in faith through the internal touch of the Savior’s wounds (John 20:29Open in Logos Bible Software (if available)). The Monthly Feasts

The believers joyfully celebrate the commemoration of the Annunciation, Nativity and Resurrection of Christ on the 29th of every Coptic month, the commemoration of St. Mary on the 21st and the feast of Archangel Michael on the 12th

The Weekly Feast

Every Sunday stands as a true Sabbath (rest), in which we find our rest in the resurrection of Christ. There is no abstention from food on Sundays after the celebration of the Eucharist, even during Great Lent.

Feasts of the Saints

There is almost a daily feast, so that the believers may live in perpetual joy and in communion with the saints. In addition there are other special fasts and occasions:

The Feasts of St. Mary: The Coptic Church venerates St. Mary as the “Theotokos,” i.e., the Mother of God, whom the Divine Grace chose to bear the Word of God in her womb by the Holy Spirit (Luke 1:35Open in Logos Bible Software (if available)). Since she is considered to be the exemplary member in the church, and the interceding mother on behalf of her spiritual children, she is exalted above heavenly and earthly creatures. Therefore, the church does not cease glorifying (blessing) her, and celebrating her feasts in order that we imitate her and ask her intercessions on our behalf Her main feasts are: The annunciation of her birth (Misra 7, c. August 13); her Nativity (Paschans 1, c. May 9); her Presentation into the Temple (Kyahk 3, c. December 12); her Dormant (Tobah 2 1, c. January 29); the Assumption of her body (Paoni 21, c. June 28); her apparition over the Church of Zeitoon (Baramhat 24, c. April 2); and the apparition of her body to the Apostles (Mesra 16, c. August 22). The Apostles’ Feast (Abib 5, c. July 12): This is the feast of martyrdom of the Apostles SS. Peter and Paul. It is preceded by a fasting period which starts on the day following the Pentecost. In this feast, the liturgy of blessing the water takes place, in which the priest washes the feet of his people (men and children) commemorating what the Lord did for His disciples. Thus, the priest remembers that he is a servant who washes the feet of the people of God and not a man of authority. The Nayrouz Feast (I st of Tout, c. September 11): The word “Nayrouz” is Persian, meaning “the beginning of the year.” The Egyptian calendar goes back to 4240 B.C. Copts restored the calendar with the beginning of Diocletian’s reign in A.D 284, to commemorate the millions of Coptic martyrs. His reign is considered a golden era in which the church offered true witnesses to Christ, when the souls of martyrs departed to paradise and kept shining as living stars therein. This feast, with its joyful hymns, continues until the feast of the Cross (Tout 17, c. 27 September). Thus the church announces her joy and gladness with the martyrs through bearing the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ. In other words, the sufferings and martyrdom were turned into a source of joy. The Two Feasts of the Cross: The first feast is on Tout 17, (c. September 27). It commemorates the dedication of the Church of the Holy Cross which was built by Queen Helen, the mother of Emperor Constantine. The second feast, is on Barmahat 10 (c. March 19) and commemorates the discovery of the Holy Cross on the hands of the same empress in A.D 326. During these two feasts the church conducts a procession similar to that of Palm-Sunday and uses the same tone in chanting (Shannon-Hosanna), to announce that the cause of her joy with the Cross is the openness of the hearts (the inner Jerusalem) to receive the Savior as the King who reigns within us. Malaty, Fr. Tadros. Introduction to the Coptic Orthodox Church (Alexandria: St. George Coptic Orthodox Church, 1987).

Coptic chant reflects one of the oldest traditions in Christian liturgical music. Some of the melodies are believed to have been adopted from Ancient Egyptian rites and practices. Additional research is needed to ascertain the true age of this ancient music and its development in the Coptic Orthodox Church.

Until recently, Coptic music was transmitted exclusively through oral repetition throughout generations. In the twentieth century, through the tireless efforts of the late Dr. Ragheb Moftah, many of these hymns were recorded by the late Master Cantor Mikhail Girgis El Batanouny and translated into traditional musical transcription by the late Dr. Ernest Newlandsmith, Martha Roy, Margit Toth, and others. Through their combined efforts, many of these ancient hymns–which would have otherwise been lost–were preserved and recorded.

The Divine Liturgy and Offerings of Incense

The core of Coptic music lies in the Divine Liturgy (Arabic: quddās), whose texts are all meant to be sung, excepting the Creed and the Dismissal. In the liturgy the most familiar hymns and chants are heard. It is basically a great music drama, consisting of three parts: (1) the Preparation; (2) the Liturgy of the Word, also called the Liturgy of the Catechumens, which comprises the Prayer of Thanksgiving, the scriptural readings, carious intercessions and responses, the recitation of the Creed, and the Prayer of Peace; and (3) the anaphora, that is, the Eucharist ritual. The entire service may require some three hours of singing, and during Holy Week, the special services may last six or seven hours.

Three liturgies have been established in the Coptic church: (1) the Liturgy of Saint Basil is celebrated throughout the year except for the four major feasts of Nativity, Epiphany, Resurrection and Pentecost; also, it is used daily in the monasteries whether there is a fast day or not; (2) the Liturgy of Saint Gregory is used today in the celebration of the four major feasts mentioned above; its music is somewhat more ornate than that of the Liturgy of St. Basil and has been characterized as the most beautiful because of its high emotion; and (3) the Liturgy of Saint Cyril, also known as the Liturgy of Saint Mark, the most Egyptian of the three.

Unfortunately, most of the melodies of the Liturgy of Saint Cyril have been lost, and it can no longer be performed in its entirety. The most recent record of its performance is that of Patriarch Macarius III (1942-1945), who used it regularly. Immediately thereafter, there may have been a few priests in Upper Egypt who remembered his manner of celebrating the anaphora. Abūnā Pachomius al-Muharraqī, vice-rector of the Clerical College, also performed it on various occasions. According to Burmester, only two chants have survived: the conclusion of the Commemoration of the Saints (“Not that we are worthy, Master…”) and an extract from the Commemoration of the Faithful Departed (“And these and everyone, Lord…”).

The celebration of the liturgy is preceded by two special services unique to the Coptic church, of which one is observed in the morning just before the liturgy and the other the previous evening. They are known as the Morning (or Evening) Offering of Incense (Arabic: Raf’ Bukhūr Bākir and Raf’ Bukhūr ‘Ashiyyah). Today, in actual practice, the Morning Offering of Incense is often incorporated into the liturgy itself. Like the liturgy, these two services are cantillated. They include the well-known Hymn of the Angels (“Let us sing praises with the angels…”), the Prayer of Thanksgiving, various prayers and responses, and other pre-anaphoral material.

The texts and rubrics for the three liturgies and the Offering of Incense are to be found in the Euchologion (Arabic: al-khūlāji), which prescribes the order of the various prayers, hymns, lections, versicles, biddings, and responses. Today these are sung in Greco-Coptic, Coptic, and Arabic. The texts are written in the Bohairic dialect (in Upper Egypt the Sahidic dialect may be heard), and are accompanied by a line-by-line translation in Arabic, with the rubrics all being in Arabic as well. The last section of the Euchologion contains the texts of many chants and hymns proper to the various liturgical seasons.

The participants in the celebration of the liturgy and Offering of Incense are:

1. The officiant, that is, the priest (Arabic: al-Kāhin), and/or other high members of the clergy who happen to be present and wish to participate. It is the role of the officient to offer the prayers (Arabic: awshiyyah, pl. awāshi), which may be recited silently or sung aloud, according to the traditional melodies adjusted to the festal and seasonal requirements. These prayers are constructed on recurring psalmodic formulas, some beginning with simple, unadorned statements, and others having an extended melisma from the outset. Since they become more and more elaborate as they continue, and conclude with a formula comprised of the richest of melismata, they may be rather lengthy. They are intones in free rhythm that generally follows textual accents and meters.

2. The deacon (Arabic: al-shammās), whose duties include relaying the biddings (Arabic: al-ubrūsāt, derived from Greek πρσευχή) of the officiant, reading the lessons, and leading the set responses and singing of the congregational hymns. Like the officiant, he cantillates in free rhythm, and his melodic line may be both rhapsodic and/or chanting. His melodies are generally more rhythmic than those of the officiant, with duple and triple metres alternating according to the textual accents. Vocalises and melismata are common, but they in no way change the basic structure of the melody.

Because some melodies of the officiant and deacon are rendered solo, there is greater opportunity here for improvisation and vocal embellishment than in choir pieces.

3. The choir and/or people (Arabic: al-sha’b) sing certain responses (Arabic: maraddāt) and portions of the hymns. In the early centuries, these sections were assigned to the people as a whole, but as the liturgy developed, they became so complicated that those who were not musically inclined could not sing them. Thus the choir of deacons, trained in singing, replaced the congregation. In the larger congregations this choir may number about twelve. The deacons involved stand by the iconostasis at right angels to the sanctuary in two lines facing each other, with one line as the bahri (“northern”), and the other as the qibli (“southern”). According to the rubrication of the “B” or “Q” marked in the margin of the text, the choir may sing antiphonally, strophe about, or two strophes about. The singers alternate according to the form of the musical phrase. They may also sing in unison.

Among many familiar choir pieces, three may be cited: (1) the hymn “We worship the Father…”, which is sung Wednesday through Saturday at the beginning of the Morning Offering of Incense; (2) the Trisagion (“Holy God! Holy and Mighty! Holy and Immortal!…”, which, according to legend, comes from a hymn sung by Nicodemus and Joseph at the Lord’s entombment; and (3) the Lord’s Prayer, which is chanted on one note.

The melodies for the people and/or choir are quite simple, with little embellishment. However, certain hymns are complicated by some rudimentary, rhythmic ornamentation integral to the composition.

As has been stated, this choral singing is monodic, and should any harmonic elements appear, they are only occasional overlappings of the incipits of one part with the finales of another. Also, the unison chant may not always be perfect, for some singers, wishing to participate in the acts of praise but not having good musical ears, do not listen to each other. Such lack of precision may be rather prevalent today, for in many churches the people, led and supported by the choir of deacons, are again actively rendering the hymns and responses, once again fulfilling the role originally assigned to them. A very wide vibrato characterizes all the singing.

Although the melodies of the participants are distinctive, as described above, there are many traits common to all. One of the most obvious characteristics of Coptic music, and one that probably derives from ancient times, is the prolongation of a single vowel over many phrases of music that vary in length and complication. This phenomenon may take two forms identified by scholars as vocalize, when the vowel is prolonged with a definite rhythmic pulse, and melisma (pl. melismata), when the vowel is prolonged in a free, undefined rhythm. A melisma generally lasts from ten to twenty seconds, but some vocalizes may continue for a full minute. Because of these many vocalizes and melismata, a study of the text alone does not always indicate the form of the music.

The music may further show its independence from the text in that musical and textual phrases do not always correspond. For example, in the Liturgy of Saint Basil, there is considerable enjambment in the solos of the priest and in the hymns sung preceding the anaphora; in some hymns a musical cadence may occur even in the middle of a word (“Judas, Judas,” herd during Holy Week on Maundy Thursday, is a case in point). In addition, the music may distort the stress and length of the syllables, especially if the text being sung is Greek.

Other traits are also prevalent. Melodies tend to proceed diatonically, usually within a range of five tones, with a characteristic progression of a half-step, whole step, and half-step, both descending and ascending. There may be intervals of thirds in the melodic line, although the distinction between the major and minor third is not always recognized as clearly as in Western music; the augmented second is rare; the diminished fourth occurs rather often. Throughout, there are numerous microtones, and therefore, many intervals can never be accurately reproduced on a keyboard instrument. Indeed, by means of these microtones, the implied tonal center of a given tune may shift imperceptibly, sometimes by as much as a minor third or more.

Many scholars have felt that Coptic melodies seem to unfold in spontaneous and endless improvisation. However, analyses reveal that this music has been constructed according to definite forms, three of which may be described. (1) Some songs are made up of various brief phrases, which are woven together so as to form clearly identifiable sections (usually three or four) and repeated with slight variation; the piece ends with a prescribed cadential formula. Concerning these compositions, Newlandsmith isolated ten musical phrases which he termed “typical.” The extended vocalizes and melismata described above are found most often in this kind of piece. (2) Other melodies are composed of longer, individual phrases, repeated as strophes and/or refrains, are sufficient for the construction of an entire hymn. (3) Some songs are made up of melodic line and rhythm that are simplified to fit the inflection and rhythm of the text. Such melodies tend to be syllabic and often have an ambitus of only two or three tones.

Some important terms, which appear in liturgical books and manuscripts to specify the music to be sung with a given text, are the Coptic `y,oc, adopted from the Greek ήχος; the Coptic bohem or ouohem, meaning “response”; and the Arabic lahn (p. alhān). Ibn Birri (1106-1187), as quoted in Lisān al-‘Arab (compiled by Ibn Manzūr, 1232-1311), assigned to lahn six meanings, among which are “song” and “psalmodizing” or “intoning.” Western scholars have translated lahn as “tone,” “air,” and/or “melody,” but non of these words conveys its full meaning. Although the term may have some affinities with the Arabic maqām and the Byzantine echos, in Coptic music it refers basically to a certain melody or melody-type which is readily recognized by the people and known by a specific, often descriptive name, such as lahn al-huzn (“… of grief”), lahn al-farah (“… of joy”), lahn al-tajniz (“… for the dead”), al-lahn al-ma’rūf (“familiar”), etc. Writing in the fourteenth century, Ibn Kabar named some twenty-six alhān, most of which are still known today. Some, designated sanawiyyah (annual), are sung throughout the year, whereas others may be reserved for one occasion only. The same text may be sung to different alhan, and conversely, the same lahn may have different texts. Furthermore, the same lahn may have three forms: short (qasir), abridged (mukhtasar), and long (tawil). Among many beautiful alhan, the sorrowful lahn Idribi may be cited as one of the most eloquent. Performed on Good Friday, during the Sixth Hour, it expresses vividly the tragedy of the Crucifixion. Its text being the Psalm versicle preceding the Gospel lection, it is also called Mazmur Idribi (Psalm Idribi). This name may derive from the ancient village Atribi, which once stood near present-day Suhaj, or it may stem from Coptic eterhybi (one causing grief). Another lahn whose name shows the antiquity of its music is lahn Sinjari, name after Sinjār, an ancient village near Rosetta.

The two melody types most frequently named are Adam and Batos (Arabic: Adām and Wātus). Hymns labeled Adam are to be sung Sunday through Tuesday, and also on certain specified days, while hymns labeled Batos are reserved for Wednesday through Saturday, for the evening service, and for Holy Week. The two names derive from the Theotokia for Kiyahk, in which Adam is the first word of the Theotokia for Monday, “When Adam became of contrite spirit…”, and Batos is the first word of the Theotokia for Thursday, “The bush which Moses saw…”. Although they are distinct from each other in verse structure, length, and mood, their music differs little in contemporary practice, and both may be heard in the same service.

The foregoing descriptions of the music and terminology used in the services of the Divine Liturgy and Offering of Incense also apply to the rest of the corpus, discussed below.

The Canonical Hours

A great wealth of Coptic hymnology may be heard in the canonical hours, which are prayers performed by lay people in the city churches and by monks in the monasteries. There are seven: First Hour, or Morning Prayer; Third Hour; Sixth Hour; Ninth Hour; Eleventh Hour, or Hour of Sunset; hour of Sleep, with its three Nocturns; and Midnight Hour. In the monasteries, the Prayer of the Veil (Arabic: salāt al-sitār) is added. The book containing these prayers is the Book of the Hours or Horologion.

The canonical hours consist of the reading of the Psalms assigned for each hour, followed by the cantillation of the Gospel, two short hymns written in strophic form, known as troparia (Greek: τροπάριον, pl. τροπάρια), plus two more troparia called Theotokia, which are an invocation to the Virgin Mary. The troparia and Theotokia are separated from one another by the Lesser Doxology, which is also cantillated. Then follow the Kyrie, the Prayer of Absolution, and throughout, responses to each part. Although troparia and Theotokia are also heard in the canonical offices of the Greek Orthodox church, their order of performance is different from that of the Copts. The Greek and Coptic melodies differ as well.

Since the hours are not dependent on priestly direction, in the towns and cities, the musical parts of each hour are led by the cantor. Formerly, in the monasteries, the monks, not being musically educated, could not intone the hours; moreover, during the early years of their development, the monastic communities rejected singing and chanting as not conductive to the reverence and piety required of their strict discipline. Today, however, many of the monks are former deacons well acquainted with the melodies of the church rites, and they cantillate the hymnic portions of the hours as prescribed. In general, the hours are in Arabic only, but in some monasteries, the monks are beginning to recite them in Coptic.

The Service of the Psalmodia

In addition to the canonical hours, there is a special choral service known as Psalmodia (Greek: Ψαλμωδία, Arabic: al-absalmudiyyah or al-tasbihah), which is performed immediately before the Evening Offering of Incense, at the conclusion of the Prayers of the Midnight Hour, and between the Office of Morning Prayer and the Morning Offering of Incense. In the monasteries, Psalmodia is performed daily, but in city churches, it has become customary to perform it only on Sunday eve, that is, Saturday night.

The texts and order of the prayers, the hymns, and lections are to be found in the book, al-Absalmudiyyah al-Sanawiyyah. Also, a special book, al-Absalmudiyya al-Kiyahkiyyah, contains the hymns to be sung for Advent, that is, during the month of Kiyahk. In both books, the basic hymn forms of this service are given as follows:

1. The hos (Coptic: hwc, derived from Egyptian h-s-j, “to sing, to praise”; Arabic: hus, pl. husat), are four special songs of praise. Burmester refers to them as odes. They comprise two biblical canticles from the Old Testament (Hos One and Hos Three) and two Psalm selections (Hos Two and Hos Four). They are strophic, with their strophes following the versification given in the Coptic biblical text. Unrhymed, they are sung to a definite rhythmic pattern, in duple meter. They are Hos One, Song of Moses (Ex. 15:1-21Open in Logos Bible Software (if available); “Then sang Moses…”); Hos Two (Psalm 136; “Give thanks unto the Lord”), with an Alleluia refrain in each strophe; Hos Three, the Song of the Three Holy Children (Deuterocanonical, Dn. 1-67Open in Logos Bible Software (if available); “Blessed art Thou, O Lord”); and Hos Four (Psalms 148, 149 and 150; all three Psalms of Hos Four may be translated as “Praise ye the Lord…” In addition, two other hos are sung for the feasts of Nativity and Resurrection, each consisting of a cento of Psalm verses.

Deriving from the ancient synagogal rites, the hos are very old. Indeed, according to Anton Baumstark, Hos One and Hos Three were the first canticles to be used in the Christian liturgy. A fragment of papyrus, brought from the Fayyum by W.A.F. Petrie, published by W.E. Crum, and identified as a leaf from an ancient Egyptian office book, contains pieces of these two hymns. Further, part of the Greek text of Hos Three has been found on an ostracon dating probably from the fifth century. From Hos Three has grown the canticle known in the West as Benedicite. Descriptions of the four hos dating from the fourteenth century, early twentieth century, and mid-twentieth century all concur, a fact that confirms the unchanged tradition of their usage. Each hos is framed by its proper Psali, Lobsh, and Tarh.

2. The Theotokia: As mentioned above, the Theotokia are hymns dedicated to the Virgin Mary. There is one set for each day of the week, with each set presenting one aspect of the Old Testament typology as it applies to Mary, the Mother of God (Greek: η θεοτόχος). The Theotokia for Saturday, Monday, and Thursday have nine sets of hymns each; those for Tuesday, Wednesday, and Friday have seven; the Sunday Theotokia (performed Saturday night) has eighteen. The strophes for all the sets of these seven Theotokia are nonrhyming quatrains, whose textual accents prescribe the rhythmic and melodic formulae. Each set has a common refrain of one to three strophes that acts as a link to unite the set. Along with each Theotokia, there are interpolations, which enlarge upon the text (Greek: έρμηνεία, “interpretation”), and every set ends with a paraphrase called lobsh. In actual practice, not all the sets of hymns in a Theotokia are performed in a single Psalmodia service because on hymn may suffice to represent the complete set.

There is a special collection of Theotokia meant to be performed only during the month of Kiyahk for Advent. De Lacy O’Leary has determined that although many of their texts resemble those of the Greek Orthodox church – especially those Greek hymns attributd to Saint John Damascene and Arsenius the monk – the Coptic Theotokia are not translations, but, rather, original poems composed on the Greek model. De Lacy O’Leary’s translation and editions of the Theotokia for Kiyahk provide ample material for analyzing the texts and comparing manuscripts. A succinct summary of their contents has been outlined by both Martha Roy and Ilona Borsai. As we mentioned above, two of these Theotokia have given their names to the melody types most commonly used throughout the liturgy and offices, namely, Adam and Batos.

Legend attributes the texts of the Theotokia to both Saint Athanasius, and Saint Ephraem of Syria while ascribing the melodies to a saintly and virtuous man, a potter by trade, who became a monk in the desert of Scetis. Euringer has identified him as Simeon the Potter of Geshir (a village in the land of Antioch); he is also known as a poet and protégé of the hymnist Jacob of Sarugh, who died in 521. This sate indicated that the Coptic Theotokia were composed in the early part of the sixth century.

Mallon, however, asserts that these works are of neither the same author no the same period. He would date them no earlier than the fifth century, but before the Arab conquest of Egypt (642-643). In the fourteenth century, Abu al-Barakat wrote that the Theotokia for Kiyahk were not used in Upper Egypt, but were passed around among the churches of Misr, Cairo, and the northern part of the country.

The lobsh (“crown,” “consummation”; Arabic lubsh and/or tafsir, pl. tafasir, “explanation, interpretation”) immediately follows a hos or a Theotokia; it is a nonbiblical text on a biblical theme. In hymn form, consisting of four-line strophes and usually unrhymed, the lobsh is recited rather than sung. However, its title designates the appropriate lahn, either Adam or Batos, which would seem to indicate that at one time it was sung.

4. The Psalis (Coptic: “praise, laudation”) are metrical hymns that accompany either a Theotokia or hos. Muyser and Yaasa ‘Abd Al-Masih have published detailed editions of certain Psalis, using manuscripts dating from the fourtheenth and eighteenth centuries. Their articles serve to demonstrate the high level of technique in handling Coptic rhymes and rhythms attained by Psali authors. Every Psali has from twenty-six to forty-six strophes, each of which is a rhymed quatrain; the rhyming schemes may vary. The strophes are often arranged in acrostic order according to the Coptic or Greek alphabet by the first letter of each strophe. Some are even in double acrostic, and others in reverse acrostic. Such patterns serve as mnemonic devices, enabling the singers to perform the hymns in their entirety with no omissions.

One feature which makes the Psalis very popular is the refrain, an element rarely found in the ritual pieces of the liturgies and canonical hours, or in the hos and Theotokia of the service of Psalmodia. Usually the refrain is made by repeating only the fourth line of the strophe, but sometimes both the third and fourth lines are repeated.

Another unusual aspect of the Psalis is that, except for a few paraphrases reserved for Kiyah, these are the only pieces of Coptic music whose authors are identified in the texts. The writer’s name may be found embedded in a strophe, with a plea for mercy and pardon from sin, and with mention of him as “the poor servant” or “a poor sinner.” In the paraphrases, the author’s name may be given in acrostic form as the first letter of each strophe of the hymn, or as the initial letter of each of a set of hymns arranged seriatim.

Most Psalis are to be sung either to the melody-type Adam or Batos, depending on the day of the week, and are thus designated as Psali Adam or Psali Batos. However, certain ones specify the title of another familiar Psali or hymn to whose melody they may be sung. These melodies are rhythmic and syllabic, that is, the notes match the texts with little trace of melisma or improvisation; their range usually covers four, or at most, five tones; they swing along in quasi-parlando style, and emphasis on textual and melodic accents makes them easy to sing, all of which encourages congregational participation. The very simplicity of these hymns leads the listener to speculate that herein lies the oldest core of ancient Egyptian melody.

A few Psalis are written in both Coptic and Greek, some in both Coptic and Arabic, and others in Arabic alone. Only one manuscript entirely in Greek has been discovered (Church of Saint Barbara, Old Cairo, History 8, 1385). Most Psalis, however, are in the Bohairic dialect, and the date of their composition in unknown. It is probable that some are no earlier than the thirteenth century. On the other hand, certain Psalis in the Sahidic dialect have been assigned to the ninth and tenth centuries (Morgan Collection, vol. XIII). These latter are in acrostic order, according to the letters of the alphabet, and they are unrhymed.

5. The tarh (pl. turūhāt) usually denotes a paraphrase used to explain a preceding hos, Theotokia, or Gospel reading. It differs from the lobsh or psali in that it is introduced with two unrhymed strophes in Coptic, which are followed by an Arabic prose text. In general, it is recited, not sung. Sometimes the same hymn is termed both Psali (Coptic) and tarh (Arabic), but, technically speaking, it may be considered a tarh when it follows the Coptic hymn of the Gospel lections. A tarh dating from the ninth century has been edited by Maria Cramer. Written in Sahidic for Palm Sunday, it was supposed to be sung. Abu al-Barakat referred to the tarh as a hymn, which further testifies to its once musical character.

6. The doxologies are hymns of praise sung during the service of Psalmodia in honor of the season, the Virgin Mary, the angels, the apostles, the saint of a particular church, or other Coptic saints, as time may allow. Their texts are similar in structure to those of the Psalis and tarh, having short strophes of four lines each and concluding with the last strophe of the Theotokia for the day. ‘Abd al-Masih has published detailed studies of the doxologies.

In additional to the foregoing, other special hymns are sung by the Copts in commemoration of their saints and martyrs. These are to be found in the Difnar or Antiphonarium (Greek: αντιφωνάριον, from αντιφωνέω, “to answer, to reply”), a book containing biographies of the Coptic saints written in hymnic form. This volume also includes hymns for the fasts and feasts. The texts are arranged in strophes of rhymed quatrains, and two hymns are given for the same saint, their use being dependent on the day of the week, that is, one for the days of Adam, and another for the days of Batos. Because these hymns are quite long, only two or three strophes may be sung during the service of Psalmodia to commemorate the saint of the day. Further, if the Synaxarion is read as a commemoration, the singing of the difnar hymn may be omitted completely.

The compilation of the difnar is ascribed to the seventieth patriarch, Gabriel II (1131-1145). However, the oldest known manuscript with difnar material dates from 893 (Morgan Library, New York, manuscript 575). Another unpublished difnar from the fourteenth century, found in the library of the Monastery of St. Antony, has been described by A. Piankoff and photographed by T. Whittemore.

Mention should also be made of the numerous ritual books that contain further repertoire to be sung for particular liturgical occasions such as the rite of the holy baptism and the rite for marriage. Each of these many rituals has its own book detailing the specifics of the rite, which of course include the use of music. Other rituals with their special books containing hymns for the specific occasions are those for the feasts and fasts of the liturgical calendar, such as the ritual for the feast of the Nativity, for the feast of Pentecost, for the fast of Holy Week, the fast of the Virgin Mary, and others too numerous to mention here.

There is one other book very important in the description of the corpus, The Services of the Deacon (Arabic: Khidmat al-Shammās), which was assembled by Abūnā Taklā and first published in 1859. This work was compiled from the various books and collections of hymns already in existence in order to assist the deacon, who, along with the cantor, has the responsibility for the proper selection and order of the hymns and responses for each liturgy and office. This book outlines the hymns and responses in Coptic and Arabic for the liturgies and canonical offices throughout the year – according to the various seasons and the calendar of feasts and fasts – and for the various rites such as weddings, funerals, baptisms, and so on.

Its rubrics are all in Arabic, but the hymn and responses are in both Coptic and Arabic. Musical terms are employed in directing the singers. The name of the lahn for each hymn and response is specified, and the rubric for the use of instruments (Arabic: bi-al-nāqūs) is also indicated where necessary. Since its first printing, The Services of the Deacon has appeared in four editions.

Moved by the spirit of prophecy, Hosea foresaw the flight from Bethlehem where there was no safe place forth Christ Child to lay his head, and the eventual return of the holy refugees from Their sanctuary in Egypt, where Jesus had found a place in the hearts of the Gentiles, when he uttered God’s words: “Out of Egypt have I called My SON “. (Hosea 11: 1Open in Logos Bible Software (if available))

In the Biblical Book of Isaiah, the prophet provides us with a divinely inspired prediction of the effect the holy infant was to have on Egypt and the Egyptians: “Behold, the Lord rides on a swift cloud, and will come into Egypt, and the idols of Egypt will totter at His Presence, and the heart of Egypt will melt in the midst of it”. (Isaiah 19: 1Open in Logos Bible Software (if available))

The authority of Old Testament prophecy, which portended the crumbling of idols wherever Jesus went, further foreshadowed the singular blessing to be bestowed upon Egypt, for its having been chosen as the Holy Family’s haven, and upon its people for having been the first to experience the Christ’s miraculous influence.

God’s message, also delivered through the prophetic utterance of Isaiah, ”Blessed be Egypt, My People ,’ (Isaiah 1 9: 25 ), was an anticipation of the coming of St. Mark to our country, where the Gospel he preached took firm root in the first decades of Christianity. For Isaiah goes on to prophecy: “in that day there Will be an altar to the Lord in the midst of the land of Egypt; and a pillar to the Lord, at its border. And it will be for a .sign and for a witness to the Lord of hosts in the land of Egypt”. (Isaiah 19: 19Open in Logos Bible Software (if available) & 20Open in Logos Bible Software (if available)). According to the traditions of the Coptic Church, ‘the altar’ mentioned is that of the Church of Virgin Mary in Al-Muharraq Monastery, a site where the Holy Family settled for a period of more than six months; and the altar-stone was the ‘bed’ upon which the Infant Savior lay.

Al Muharraq Monastery is located, literally, “in the midst of the land of Egypt”….standing at its exact geographical center. As for the “pillar at its borders…. which will be for a sign and for a witness…” surely there can be no more demonstrable, concrete proof of the fulfillment of the prophecy than that the Patriarchal See of the Apostolic Church in Egypt, established by St. Mark himself, is situated in Alexandria, on Egypt’s northern borders.

But the prophecy, knitting a perfect pattern of things to come, does not stop there. It continues, “Then the Lord will be known to Egypt, and the Egyptians will know the Lord in that day and will make sacrifice and offering”. (Isaiah 19: 21Open in Logos Bible Software (if available)).

As Christianity in Egypt spread, churches were built throughout the length and breadth of the land, and the sites chosen were, primarily, those which, had been visited and blessed by the Holy Family’s sojourns. The New Testament records the fulfillment of these Old Testament prophecies as they unfold in their historical sequence.

“…….behold, an angel of the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream, saying, Arise, take the young Child and His mother, flee to Egypt, and stay there until I bring you word, for Herod will seek the young Child to destroy Him “. (Matthew 2 :13).

Joseph complied. A donkey was fetched for the gentle Mother, still so young in years, to ride with her new-born Child in Her arms. And so they set out from Bethlehem on their predestined journey, the hardened old carpenter, who was Mary’s betrothed, striding ahead, leading the donkey by its leash into the untracked paths of a wilderness dark as the desert nights, and unending as the months of never ending horizons.

Such an arduous journey it was, fraught with hazard every step of the way. In those far-off days, there were three routes which could be followed by travelers traversing Sinai from Palestine to Egypt, a crossing which was usually undertaken in groups, for without the protection of well-organized caravans, the ever-present dangers – even along these known and trodden paths-were ominously forbidding.

But, in their escape from the infanticidal fury of King Herod, the Holy Family – understandably – had to avoid the beaten tracks altogether, and to pursue unknown paths, guided by God and His Angel.

They picked their way, day after day, through hidden valleys and across uncharted plateaus in the (then) rugged wastelands of Sinai, enduring the scorching heat of the sun by day and the bitter cold of the desert nights, preserved from the threat of wild beasts and savage tribesmen, their daily sustenance miraculously provided, the all-too-human fears of the young Mother for her Infant allayed by the faith that infused her with His birth.

And so they arrived, at last, safely, for God had pre-ordained that Egypt should be the refuge for the One who was to bring the message of peace and love to mankind.

The tortuous trails they followed in their passage across Sinai, and their subsequent travels within Egypt, are chronicled by Pope Theophilus, 23rd Patriarch of Alexandria (384 – 412 AD). He testifies, in his celebrated annals, that on the eve of the 6th of Hathor (the Coptic month corresponding roughly with November), after long prayer, the Holy Virgin revealed herself to him and, after relating the details of the Holy Family’s journey to, in, and from Egypt, bade him record what he had seen and heard. It is a source which no Christian believer would question.

Besides, it is a virtual certainty that, at a time when happenings of a momentous or historical nature were transmitted by word of mouth from one generation to the next, the account of Pope Theophilus’s vision confirmed the oral tradition of supernatural occurrences which accompanied the arrival of a wondrous Child in the towns and villages of Egypt some 400 years earlier.

It was at the house of Saint Mark that the Lord met with His Apostles and celebrated the Passover, where the Lord appeared to them after His Resurrection, and where the Holy Spirit descended upon the Apostles on the Day of Pentecost. Thus, it is well known by all the Apostolic Churches as the first church in the world. Hence, the Coptic Church is one of the oldest churches in the world, spanning 20 centuries of history. By the end of the second century, Christianity was well established and very active in Egypt.

The Coptic Orthodox Church is one of the five most ancient churches in the world and is called the “See of Saint Mark.” The other four ancient sees are the Church of Jerusalem, the Church of Antioch (Antiochian Orthodox Church), the Church of Rome (Roman Catholic Church) and the Church of Athens (Greek Orthodox Church).

The first mention of Egypt in the Old Testament is in Gen 12:10Open in Logos Bible Software (if available), where we are told that “there was a famine in the land: and Abram went down into Egypt to sojourn there.” Egypt is mentioned once again in Gen 13:10Open in Logos Bible Software (if available): ”And Lot lifted up his eyes, and beheld all the plain of Jordan, that it was well watered every where, before the LORD destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah, even as the garden of the LORD, like the land of Egypt.”

Egypt was a land of plenty, described as being even as the garden of the Lord. The Lord allowed Joseph to be sold to the Egyptians by his brothers, in order to bring Israel and his children into Egypt, where for more than 400 years, the church of the Old Testament would be nurtured in Egypt.

When the time came for the Lord to bring His people out of Egypt, he allowed Moses to be raised by Pharaoh’s daughter, and we are told “And Moses was learned in all the wisdom of the Egyptians.” (Acts 7:22Open in Logos Bible Software (if available))

But the major story about Egypt in the Old Testament is without a doubt the story of Exodus. A simplistic way of looking upon the Exodus account is to view it as a good guys versus bad guys story, the good guys win and the bad guys loose. If, on the other hand we look more carefully at the account in Exodus, we will find a totally different story emerging.

In Exodus 7:3Open in Logos Bible Software (if available), the Lord tells Moses, “And I will harden Pharaoh’s heart, and multiply my signs and my wonders in the land of Egypt.” One may wonder, why would the Lord harden Pharaoh’s heart, and then punish the Egyptians by visiting the ten plagues upon them? But the answer to this query comes in Exodus 7:5Open in Logos Bible Software (if available), where the Lord explains, “And the Egyptians shall know that I am the Lord, when I stretch forth mine hand upon Egypt, and bring out the children of Israel from among them.”

The key verse here is, “And the Egyptians shall know that I am the Lord.” This was God’s plan for the salvation of the Egyptians. The Lord wanted to bring them into His fold. But the Lord knew that the Egyptians were stubborn and proud and that the only way to bring them into His fold was to bring them to their knees.

Again, in Exodus 14:4Open in Logos Bible Software (if available) “And I will harden Pharaoh’s heart, that he shall follow after them; and I will be honoured upon Pharaoh, and upon all his host; that the Egyptians may know that I am the Lord.

Exodus 14:17Open in Logos Bible Software (if available) “And I, behold, I will harden the hearts of the Egyptians, and they shall follow them: and I will get me honour upon Pharaoh, and upon all his host, upon his chariots, and upon his horsemen. And the Egyptians shall know that I am the Lord.”

In a most emphatic way, the lord tells Moses that the Egyptians shall know that I am the Lord. And it worked, for when the Lord troubles the host of the Egyptians and takes off their chariot wheels (Ex 14:24Open in Logos Bible Software (if available),) the Egyptians said, Let us flee from the face of Israel; for the Lord fighteth for them. (Ex 14:25Open in Logos Bible Software (if available))

A similar encounter between the Egyptians and the Lord happened 900 years later, in the time of Ezekiel and Jeremiah. When Nebuchadnezzar set siege to Jerusalem, the Egyptians incited the Israelis to resist, promising them military assistance. This was contrary to the word of the Lord through Jeremiah, who told the Israelis to submit themselves to the yoke of Nebuchadnezzar, for the Babylonian exile was fore-ordained by the Lord. The Egyptians were thus a stumbling block unto Judah, and for this the Lord visited them with another set of plagues that are described in the Book of Ezekiel.

In Ez. 29:3-6Open in Logos Bible Software (if available) the Lord says, “Behold, I am against thee, Pharaoh king of Egypt, the great dragon that lieth in the midst of his rivers, which hath said, My river is mine own, and I have made it for myself. But I will put hooks in thy jaws, and I will cause the fish of thy rivers to stick unto thy scales, and I will bring thee up out of the midst of thy rivers, and all the fish of thy rivers shall stick unto thy scales. And all the inhabitants of Egypt shall know that I am the Lord” The same words used in Exodus are used here.

Ez. 29:9Open in Logos Bible Software (if available) “And the land of Egypt shall be desolate and waste; and they shall know that I am the Lord.” Ez. 30:8Open in Logos Bible Software (if available) “And they shall know that I am the Lord, when I have set a fire in Egypt, and when all her helpers shall be destroyed.” Again and again we are told that the object of these plagues is to bring the Egyptians to the knowledge of the Lord. Ez. 30:13Open in Logos Bible Software (if available),19Open in Logos Bible Software (if available) “Thus saith the Lord God; I will also destroy their idols, and I will cause their images to cease out of Noph; and there shall be no more a prince of the land of Egypt: and I will put a fear in the land of Egypt. Thus will I execute judgments in Egypt: and they shall know that I am the Lord.” Here it becomes more clear, I will destroy their idols and cause the images to cease, a strong indication of the conversion of the Egyptians from idol worship to the knowledge of the Lord.